All my life I’d assumed that

the famous Cumberland Gap--from when our western frontier was the Appalachians,

which run from Canada down to Alabama--was somewhere north of Virginia,

like along the valley of one of the three rivers at Pittsburgh or likely

around the well-named town of Cumberland in western Maryland! Nope.

Now

it occurs to me that perhaps a lot of other people don’t know where

it is. Thus this article.

The

Name. You folks of Scottish ancestry won’t like this, but the name

comes from Prince William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, third son of King

George II of England, and uncle and close advisor to good old George III.

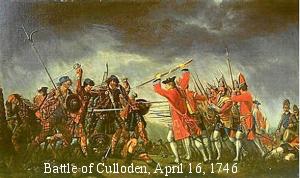

Prince William led the English army against the Jacobite rebellion of Bonnie

Prince Charlie at the 1746 Battle of Culloden. While the Scot Jacobites

depended mostly upon swords, the English had bayonets. And English army

procedure in the inaccurate musket days was to just shoot once, not take

time to reload, and immediately sweep the field with a disciplined bayonet

charge (which also worked pretty well for them in the American Revolution

against colonial volunteers). At Culloden, English soldiers used their bayonets

against the Scottish swordsman engaged with the Englishman on their right.

Result: about 1,500 Scots killed vs 100 English. The

Name. You folks of Scottish ancestry won’t like this, but the name

comes from Prince William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, third son of King

George II of England, and uncle and close advisor to good old George III.

Prince William led the English army against the Jacobite rebellion of Bonnie

Prince Charlie at the 1746 Battle of Culloden. While the Scot Jacobites

depended mostly upon swords, the English had bayonets. And English army

procedure in the inaccurate musket days was to just shoot once, not take

time to reload, and immediately sweep the field with a disciplined bayonet

charge (which also worked pretty well for them in the American Revolution

against colonial volunteers). At Culloden, English soldiers used their bayonets

against the Scottish swordsman engaged with the Englishman on their right.

Result: about 1,500 Scots killed vs 100 English.

Not only did he destroy the rebel army, but “Butcher Cumberland”

ordered his troops to take no prisoners. Injured rebels were stabbed where

they lay. Then the English government began the “Highland Clearances”

to break up the Scottish clan culture, including offering transportation

to North America in exchange for the signing of an oath of loyalty to the

crown. Great numbers of Scots settled in Virginia and the Carolinas, including

up the Cape Fear River valley from Wilmington, NC into the Chapel Hill area

where we live. During the American Revolution, many of these honor-bound

Scottish loyalists contributed to the most terroristic fighting of the war

(see the movie “The Patriot” with Mel Gibson). Many of these Scottish

loyalists also moved to Canada, which beat being tarred & feathered

by the “rabble in arms.”

The

English thought Cumberland’s 1746 victory over the wild Scots and their

awful French allies was just wonderful. English governors in the American

colonies rushed to honor their latest hero. Thus we have Cumberland counties

in Maine, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, North Carolina, Kentucky, and Tennessee. The

English thought Cumberland’s 1746 victory over the wild Scots and their

awful French allies was just wonderful. English governors in the American

colonies rushed to honor their latest hero. Thus we have Cumberland counties

in Maine, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, North Carolina, Kentucky, and Tennessee.

Small world: In 1755, as English army commander-in-chief, Cumberland appointed

Major General Edward Braddock to command all English forces in North America.

Braddock’s primary task was to defeat French forts enforcing France’s

claim to the Ohio River Valley. Wagons and supplies for Braddock’s

army were procured by the initiative of a Philadelphian named Benjamin Franklin.

From the U.S. National Archives: “In two weeks Franklin had 150 wagons

and 259 horses, with more coming in daily. ‘With the Assistance we

have had from Mr. Franklin, who is almost the only Person to whom the General

is indebted for either Waggons or Horses,’ Braddock’s secretary

wrote gratefully on May 21, 1775, ‘we hope to get over the Mountains.’”

Braddock led his 2,100-man force on rough dirt roads through the forested

Allegheny Mountains to attack Fort Duquesne (located in what today is downtown

Pittsburgh). Ambushed by a French and Indian force in the trees, Braddock’s

battlefield-trained redcoats panicked and ran, and Braddock was mortally

wounded. Braddock had a colonial aide-de-camp named Lieutenant Colonel George

Washington, age 23, who later wrote to his mother: “I luckily escaped

without a wound, though I had four bullets through my coat, and two horses

shot under me.” Back in Braddock’s wagon train were two young

drivers named Daniel Boone and Daniel Morgan (later commander of the victorious

Patriots at the Battle of Cowpens, and key inspiration for the Mel Gibson

character in “The Patriot”).

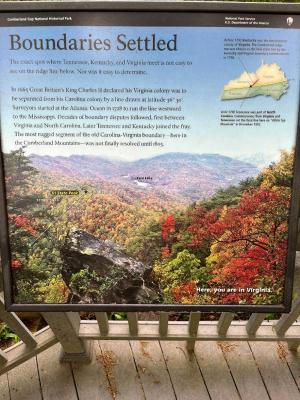

Location. The Cumberland Gap is right where Virginia, Kentucky and Tennessee

come together. Think of “the camel’s nose” in the shape of

Virginia. Simply: right on the nose.

Enter

Boone. The Shawnee Indians who hunted and fought in much of what is today’s

Kentucky were defeated by the British in the 1774 Lord Dunmore’s War.

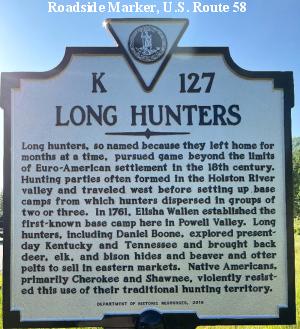

In 1775, the year of the Battles of Lexington and Concord, “long hunter”

Daniel Boone of Yadkin Valley, NC (west of today’s Raleigh-Durham-Chapel

Hill triangle), told his friend, land speculator and Judge Richard Henderson,

that the Cherokee wanted to explore selling their hunting grounds west of

the mountains. Henderson then led Boone and others in negotiating and signing

the March 17, 1775 Treaty of Sycamore Shoals, by which Henderson’s

Transylvania Company paid some 10,000 British pounds sterling worth of trade

goods to the Shawnee for lands ranging from parts of today’s West Virginia,

southwest Virginia, much of Kentucky and northern Tennessee (including what

became Nashville). Enter

Boone. The Shawnee Indians who hunted and fought in much of what is today’s

Kentucky were defeated by the British in the 1774 Lord Dunmore’s War.

In 1775, the year of the Battles of Lexington and Concord, “long hunter”

Daniel Boone of Yadkin Valley, NC (west of today’s Raleigh-Durham-Chapel

Hill triangle), told his friend, land speculator and Judge Richard Henderson,

that the Cherokee wanted to explore selling their hunting grounds west of

the mountains. Henderson then led Boone and others in negotiating and signing

the March 17, 1775 Treaty of Sycamore Shoals, by which Henderson’s

Transylvania Company paid some 10,000 British pounds sterling worth of trade

goods to the Shawnee for lands ranging from parts of today’s West Virginia,

southwest Virginia, much of Kentucky and northern Tennessee (including what

became Nashville).

Henderson then hired Boone to lead 30 axe men to blaze an improved trail

along the old Indian Warriors’ Trail from what is now Kingsport, TN

along the Virginia border through the Cumberland Gap into Kentucky. Boone’s

Wilderness Trail connected to the Frontier Trail coming southwest from Roanoke,

VA, which in turn joined the Great Valley Road that carried recent immigrants

from the seaport of Philadelphia down the Shenandoah Valley. Collectively,

these three segments today are known as The Wilderness Road. It would not

be until 1794 that Boone’s Wilderness Trail would be improved to the

point of opening to wagon traffic. Folks walked, rode animals, or at most

had handcarts.

Small world: My sophomore year in high school was at Henderson City High

School, Henderson, KY (on the Ohio River across from Evansville, IN), named

in Richard Henderson’s honor.

Impact. Between 1776 and 1810, over 200,000 settlers came through

the Cumberland Gap--then the primary population route to the American West--into

Kentucky and the Ohio River Valley. And by 1792 Kentucky became our 15th

state.

By 1800, Cumberland Gap traffic on the Wilderness Trail went both ways,

as western farmers herded thousands of cattle, pigs, sheep, and turkeys

(!) back to eastern markets. Oh, and they also brought profitable corn whiskey--many

drawing upon distilling & tax-avoidance expertise they’d learned

in the Highlands of Scotland--which remain today the core of robust Scottish

whisky production (note the different spelling in Scotland [and Canada and

Japan] from Ireland and the USA--no “e”).

By the 1830s, better roads, canals, and early railroads lessened the importance

of the Wilderness Road and Cumberland Gap as a route westward. In 1889,

a railroad tunnel was completed under the Gap. In the 1920s, U.S. Highway

25E was built through the Gap. And in 1996 the U.S. 25E highway tunnel was

completed, bypassing the Gap, after which the landscape of the Gap was restored

to about its appearance in 1810. This is where I walked.

Settlement.

Looking down from the mountains into Kentucky, Boone and his 1775 crew found

bountiful herds of bison, elk, deer, et al in lush natural bluegrass meadows

north of “The Narrows” of the Cumberland River by what is today’s

Pineville, KY. He then decided to return home and bring back his family,

and to establish a settlement. Settlement.

Looking down from the mountains into Kentucky, Boone and his 1775 crew found

bountiful herds of bison, elk, deer, et al in lush natural bluegrass meadows

north of “The Narrows” of the Cumberland River by what is today’s

Pineville, KY. He then decided to return home and bring back his family,

and to establish a settlement.

Unfortunately, only a month after Henderson paid his 10,000 pounds in goods

to buy these lands, the April 19, 1775 Battles of Lexington and Concord

kicked-off the American Revolution. Settlers coming in sided with the Patriots.

The Shawnee sided with the British. Now the Patriots had to fight for what

they’d already paid the Shawnee to have. This fighting would cost Daniel

Boone a brother and two sons killed.

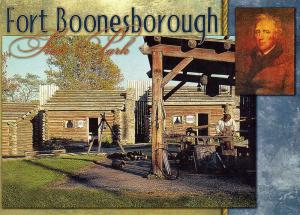

With his family, relatives and friends, Daniel Boone founded Fort Boonesborough,

on the banks of the Kentucky River southeast of today’s Lexington,

KY. He lived there 1775-1779, fighting to defend it constantly, including

during the Siege of Boonesborough in 1778. In 1779, Boone led a migration

group to Boonesborough that included one Abraham Lincoln, grandfather of

the future president. Boone’s route from Cumberland Gap up to Lexington,

KY is today known as Boone Trace.

Here I’ll leave your interest in the story of Daniel Boone to the many

good books about him. I can recommend one that classmate Chuck led me to:

about Boone’s long-distance pursuit and rescue of his daughter Jemima

after she was captured by Indians. “The Taking of Jemima Boone,”

by Matthew Pearl, is available on Amazon. Excellent history and exciting

adventure. Boone really was a hero, smart and fearless. Jemima, age 13 on

July 14, 1776 when she was kidnapped (yes, 10 days after Independence Day),

was smart and fearless, too.

My Trip. Inspired by watching Ken Burns’ two-part documentary “Daniel

Boone and the Opening of the American West,” (free on YouTube.com),

and remembering how much I enjoyed driving the Lewis & Clark route from

Cahokia, IL to the mouth of the Columbia River on the Pacific (www.usafa68.org,

click on Bulletins, then click on Bulletin #28), I decided to make the easy

drive northward from our home in Chapel Hill to see what is out there today

along Boone’s Wilderness Trail route. This trip was done May 20-21,

2022.

The drive from Chapel Hill to Wytheville, VA was a pleasant couple-hour

approach from our piedmont toward the mountains. Wytheville is at the intersection

of I-77 coming up from North Carolina and I-81 which follows the Wilderness

Road route through the Shenandoah Valley down to Bristol, VA on the Tennessee

border. Wytheville has an excellent visitor center for tourists, with lots

of good literature. In Wytheville is a historic gas station, built in 1926,

on old Route 23, then known as the Great Lakes to Florida Highway. Shot

Tower Historical State Park is nearby, near a lead mine developed in 1757.

Stephen Austin was born near this mine (and Sam Houston was born up in Lexington,

VA in the Shenandoah Valley, migrated down the Wilderness Road with his

family, became governor of Tennessee, and then moved on to Texas).

In

the town of Abingdon, VA, along I-81, I stopped to look at the 4-star Martha

Washington Inn and Spa, nicely renovated but retaining its squeaky wood

floors. Built in 1832 by General Francis Preston as a family home, in 1858

it became Martha Washington College for Women. During the Civil War it also

served partly as a hospital for both Confederate and Yankee wounded--and

of course generated love stories about some of its students and those soldiers. In

the town of Abingdon, VA, along I-81, I stopped to look at the 4-star Martha

Washington Inn and Spa, nicely renovated but retaining its squeaky wood

floors. Built in 1832 by General Francis Preston as a family home, in 1858

it became Martha Washington College for Women. During the Civil War it also

served partly as a hospital for both Confederate and Yankee wounded--and

of course generated love stories about some of its students and those soldiers.

At Bristol, VA, on I-81, I stopped to look at the renovated old Bristol

Hotel in downtown.

Bristol also claims to be the birthplace of country music--and has a museum

to prove it right next door to the Bristol Hotel.

I then followed the valleys over to Kingsport, TN just across the border,

and just north of Kingsport began my drive on U.S. Route 58 along the countryside

that Daniel Boone walked, to and through the Cumberland Gap at the “camel’s

nose” of Virginia.

As you get closer to the mountains on Route 58, local farmers clearly must

get more creative with their pasture lands. It looks like their cows might

need to have two long legs and two short ones on the other side:

Farther west on Route 58, in Ewing, VA, is historic Martin’s Station

in Wilderness Road State Park. Judge Henderson appointed settler Joseph

Martin to be his agent in guiding settlers toward his Transylvania Company’s

lands west of Cumberland Gap. Martin’s Station was the last fortified

point in Virginia before the settlers passed into these frontier lands,

so it was well-known and appreciated by them. Today the site is a pleasant

and well-maintained park.

Driving

on toward the Cumberland Gap, it’s not an obvious hole in the mountains. Driving

on toward the Cumberland Gap, it’s not an obvious hole in the mountains.

And when Route 58/U.S. 25E reaches the Gap, your first surprise is when

it goes through the long 25E Cumberland Gap Tunnel through Tri-State Peak

from Virginia into Middlesboro, KY, by the entrance to Cumberland Gap National

Historical Park. Middlesboro (home from the age of two of Lee Majors, The

Six Million Dollar Man of 1973-78 TV fame), has lots of motels and restaurants,

and was the first town in the nation to use a city manager form of government.

And when Route 58/U.S. 25E reaches the Gap, your first surprise is when

it goes through the long 25E Cumberland Gap Tunnel through Tri-State Peak

from Virginia into Middlesboro, KY, by the entrance to Cumberland Gap National

Historical Park. Middlesboro (home from the age of two of Lee Majors, The

Six Million Dollar Man of 1973-78 TV fame), has lots of motels and restaurants,

and was the first town in the nation to use a city manager form of government.

There’s a pleasant visitor center in the park, with films about Cumberland

Gap and about Daniel Boone, plus the usual displays about natural life in

the region, and a gift shop. Just outside the visitor center parking lot,

you pick up the road to Pinnacle Overlook, which has a lot of tight switchbacks

but is superbly paved and marked. Go to the top first, to get the “big

picture.”

Walking

the short distance from the top parking lot to the Overlook, you cross the

state line: Walking

the short distance from the top parking lot to the Overlook, you cross the

state line:

And you pass a side walkway that in wintertime (when these trees don’t

have leaves) you can look down to where the three states come together.

For summertime, this helpful sign is provided:

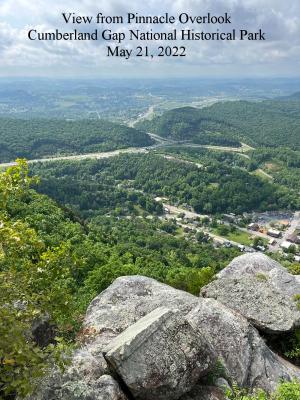

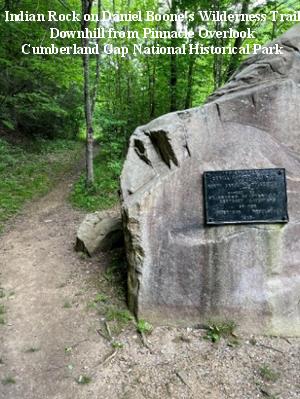

Looking down from the top of Pinnacle Overlook (first photo in this article),

the modern highway route through the hills is obvious, but that’s not

where Daniel Boone walked. His Wilderness Trail actually followed along

the side of the mountain you’re on, about 240’ above the highway

level below (see Indian Rock photo above). You can walk where Boone walked

by stopping at another parking lot halfway down Pinnacle Overlook Road.

During

your walk toward Boone’s actual trail, you’ll traverse a segment

of a 1907 “Object Lesson Road,” which was part of a federal initiative

around the country to demonstrate to voters the value of improving dirt

roads with gravel. By 1907, only 11 automobile trips across the USA had

been recorded. The USA had 328,000 miles of railroad track, but only 8,000

cars and only 144 miles of paved roads (and only 14% of homes had an installed

bathtub, so fortunately your automobile provided lots of fresh air…).

This was the same year that Henry Ford began developing his Model T, which

he began to sell in 1908. Gravel on a road was pretty high-tech. During

your walk toward Boone’s actual trail, you’ll traverse a segment

of a 1907 “Object Lesson Road,” which was part of a federal initiative

around the country to demonstrate to voters the value of improving dirt

roads with gravel. By 1907, only 11 automobile trips across the USA had

been recorded. The USA had 328,000 miles of railroad track, but only 8,000

cars and only 144 miles of paved roads (and only 14% of homes had an installed

bathtub, so fortunately your automobile provided lots of fresh air…).

This was the same year that Henry Ford began developing his Model T, which

he began to sell in 1908. Gravel on a road was pretty high-tech.

Perspective on roads: As late as 1919, a young Army officer named Dwight

Eisenhower was a volunteer tank officer who participated in an Army truck

convoy to test driving across the country from Washington, D.C. to San Francisco.

Eisenhower wrote in his book At Ease: Stories I Tell to Friends that, “In

those days, we were not sure it could be accomplished at all. Nothing of

the sort had ever been attempted.” Highway pavement was still rare.

My own father was 10 years old. The 81-vehicle Army convoy, led by scouts

riding Harley-Davidson and Indian motorcycles (who drew arrows in the dirt

to point the right direction), took 62 days. As explained by the History

Channel in its article “The Epic Road Trip that Inspired the Interstate

Highway System”…

“As Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces in World War II, Eisenhower

saw first-hand how Nazi Germany’s high-speed autobahn network allowed

its troops to mobilize quickly to fight on two fronts. ‘After seeing

the autobahns of modern Germany and knowing the asset those highways were

to the Germans, I decided, as president, to put an emphasis on this kind

of road building,’ Eisenhower wrote. The 1919 trip, however, also remained

in the forefront of his mind. ‘The old convoy had started me thinking

about good, two-lane highways, but Germany had made me see the wisdom of

broader ribbons across the land.’ With America’s roads remaining

in poor condition decades after his arduous cross-country trip, Eisenhower

championed the creation of the American Interstate Highway System, which

was officially named in his honor in 1990.”

That

Interstate Highway System got me to Cumberland Gap. Daniel Boone would’ve

been proud. He showed the way. That

Interstate Highway System got me to Cumberland Gap. Daniel Boone would’ve

been proud. He showed the way.

I hope you enjoyed this little note. And if you have another fun trip with

some historical significance to recommend, please do!

Bill Eckert

billsueeckert@aol.com

May 27, 2022 |